INTERVIEW: Painter Juan Arango Palacios on tenderness, symbolism and being neither here nor there

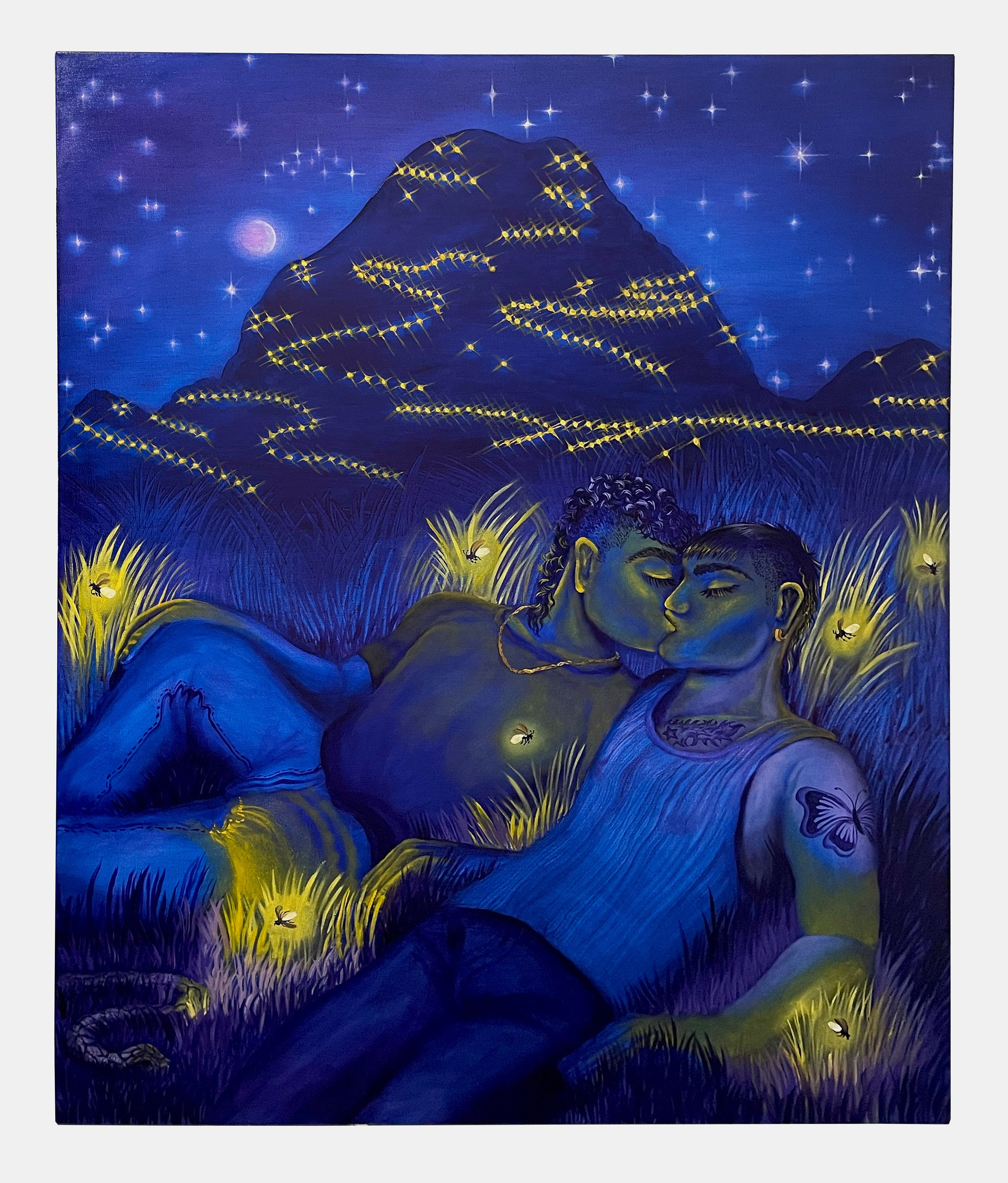

“Beso Frente al Alto,” 2024. Courtesy of Juan Arango Palacios.

A warm embrace under the night sky. Tender kisses in the summertime. Hands hidden in a lover’s back pocket. These are just a few of the images that Chicago-based painter Juan Arango Palacios brings to life with his vibrant, figurative style. His works are colorful, intimate and vulnerable, telling the stories of his experience navigating life as a queer Colombian immigrant.

Born in 1997 in the small coffee-growing region of Pereira, Palacios has lived numerous lives—as a child in Colombia and rural Louisiana, as a teenager in a picturesque Dallas suburb and eventually, as an adult in the city, studying art and graduating from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

After nearly a decade, Palacios says Chicago has become integral to who he is as an artist. With his narrative paintings, Palacios provides fragments of his inner-world, weaving a symbolic structure that dissects the relationship to his heritage, his culture and his queerness.

Fresh off his solo exhibition, “Ninfo, Te Quiero,” in Bordeaux, France, Palacios will begin a residency in Los Angeles, CA, in May. Palacios has shown around the world including New York City, Miami, London and the Dominican Republic. He currently has a tapestry permanently installed at the Epiphany Center for the Arts in Chicago.

Palacios talked to Mustard about his experience moving to the United States as a child, his approach to art and how he’s currently working to build a community that resonates both inside his work, and out.

Juan Arango Palacios. Courtesy of Diana Solis.

Mustard Magazine: You’ve lived in Colombia, Louisiana, Texas and Chicago. What has it been like navigating these vastly different environments?

Juan Palacios: Even though American culture is much different from Colombian culture, [culture in Louisiana] is derived from French culture, so there’s a few similarities there. It’s also heavily Catholic. I grew up Catholic, so there’s a lot of weird similarities.

The school that my brother and I attended, we were the only two Spanish-speaking people there. So we were really forced to just learn English. There was no ESL program because there was no demand for it. However, at the same time we were learning English in Louisiana, they also teach kids French, so I started taking French classes and learning English and French at the same time.

Even though the rest of America has this perspective that Louisiana is conservative—which it definitely is—I didn’t really ever feel discriminated against, at least blatantly. There were definitely microaggressions here and there, but southern hospitality definitely is a thing and I really experienced that and felt welcomed by the community there.

When I left Louisiana, we were living in a rural tiny town of less than 2,000 people, so I was used to these vast rice and sugarcane fields. My brother and I would sometimes go to my parents' work and we would get to ride tractors and stuff like that.

When I moved to Texas, I moved to [the suburbs], so it was a huge culture and environment shift. It was a really diverse place. There were Asian students, Indian students—a big Mexican community. In Louisiana, it was just Black and white. It was nice to be in this environment where I was introduced to new cultures and new people that I had never experienced before.

“Lover’s Dream,” 2025. Courtesy of Juan Arango Palacios.

MM: When did you first get into painting?

JP: I’ve drawn my whole life, since I was very young. The moment I knew I wanted to be an artist, it’s a really vivid memory that lives in my mind. I was in Colombia in the third grade, and there was this art competition in my school where they gave us a prompt and we had to make a drawing and the winner would win this toy. I ended up winning the competition.

This is Colombia, so it was a Catholic school, and my teacher knelt down next to me and was like, “Juan, God has given you a gift and you have to pursue it.” I guess that’s the first time that my skill as an artist was ever recognized by someone other than mom or my grandma, so it made me take it more seriously and it made me realize that that’s what I want to do with my life.

MM: Can you talk about your approach to your work?

JP: Composition is really important to me, and I also really focus on vivid color palettes. I like to overlay colors with a really low opacity so that colors can interact with each other without me necessarily having complete control over what the color will do on the canvas.

Something else that’s really important in my work as well is accessibility. Visually speaking, I want my work to be easily accessible by anyone who sees it, especially people who don’t have a background in art. I feel like a lot of artists make art for other artists who have a fancy art degree, who have read abstract art theory, but I want my work to speak not only to artists but also to people like my mom or my grandmother, or my neighbor in my community who hasn’t even graduated high school.

I want my paintings to be able to speak to a really broad audience, and that’s why I feel like the figure is so important to me, because when we see ourselves and our bodies in this work, we can at least have some sort of reaction to it that is more relatable than just pure abstraction.

Chicago-based painter Juan Arango Palacios stands in front of his current work-in-progress, “An Ode to Old Friends,” inside his studio. Courtesy of Mustard Magazine.

MM: You’re currently working on a new piece. What can you share about the symbolism behind it?

JP: This painting is about friendship. I think it’s going to be titled, “An Ode to Old Friends.” It’s about my experience with friendship, both negative and positive experiences I’ve had. I am mourning the loss of specific friends in my life. I feel like it’s something we just deal with as adults, you just lose friends. At both edges of the canvas, there’s a figure walking in and a figure walking out, sort of symbolizing the passing nature of friendship in general.

Palacios shows how to use a loom inside his art studio. Courtesy of Mustard Magazine.

The narratives are rooted in all aspects of my life—the mountains very much symbolizing where I come from, Colombia. The volcano, clearly a sign of conflict, but they’re in the background and almost seem like this pillar that is far away—the same way that it lives in my memory. It’s not something that’s very vivid, it’s something that’s kind of blurred and behind me.

The cowboy and the truck come from my experience as an artist in Texas and in Louisiana. Trucks have always been this symbol of masculinity, and I both admired and was intimidated by that, and so I wanted to include that symbol in my painting.

At the bottom I’m making an art-historical reference to Narcissus. Narcissus has been a subject of many classical paintings, the Greek myth of Narcissus looking at himself in the mirror and being so obsessed with his own image that he rotted and died there looking at himself, so this sort of introspective self-critique. “Do I see myself in my friends? Are my friends a reflection of me?” [That’s the] sort of the reference that I’m making there.

MM: What are some recurring symbols in your work?

JP: When I was in school I took a class about migration in art history and we read Walter Benjamin, and he has an essay on immigration. Something that really stuck with me from that reading was this statement about how as an immigrant, when you leave your homeland to move somewhere else, the moment that landscape is no longer behind you, it changes forever. It’s just never the same, even if you come back to visit or live, and that’s something that really stuck with me.

Drawings inside the artist’s Chicago studio. Courtesy of Mustard Magazine.

I feel like Colombia definitely has changed. I also struggle a lot with this immigrant sentiment of, ‘I’m not from here and I’m not from there.’ Like, I never feel American enough in America and I never feel Colombian enough in Colombia. My family sees me as the American cousin who just like, is now American, you know?

I have “Ni de aquí, ni de allá,” tattooed—“Neither from here, neither from there”—because that is how I feel. I don’t feel American, I don’t feel Colombian, it’s this weird in-between identity. And I kind of use that to my advantage. I will place people, places and things that I have encountered or met at different times in my life in different places and put them together. Like these trucks, these cowboys, the mountains, they’re all living in my world, so I kind of bring my entire experience as a whole into its own little world to create what I call my mythos around my immigrant experience.

MM: In addition to the immigrant experience, your paintings often explore intimate depictions of queer love. How is this an integral part of your art?

JP: As a queer person I feel like it is mostly a matter of representation. Back in 2016, I wouldn’t have considered being gay or being queer to be radical, but now it very much is, because of the current political period that we’re living in. So I do see queer representation to be really important, and try to make my paintings unapologetically queer, unapologetically gay.

My work tends to focus on moments of tenderness. A lot of historical queer art has focused on hyper-sexualization of queer bodies, which I think was very efficient and successful for its time, this kind of like, “Hey, we exist and we don’t care what you think.” But now I much prefer focusing on the moments that people don’t see or think about, these tender moments.

I have a lot of work [featuring] cuddling, hugging, kissing. Thinking about the very possible outcome of me not being able to get married anymore—it just seems like it’s inevitable and looming, like they’re going to overturn [gay marriage] like they already overturned abortion. I may not have the possibility to get married, and so these images are extremely important to exist, and they’re going to exist regardless of whether they’re allowed to or not, and I think it’s my responsibility to make them exist for that reason.

“Steam Room,” 2023. Courtesy of Juan Arango Palacios.

MM: You’ve mentioned previously that music is central to your paintings.

JP: Music is really important to my work. I listen to a lot of cumbia and reggaeton, but if you put on the radio right now, 90 percent of the songs on the radio are going to be [about] love or heartbreak. Taylor Swift is a billionaire from writing about heartbreak, but for some reason when we talk about these things in a fine art context it’s seen as juvenile or not academic enough, and it’s seen as less-than.

There’s this expectation that art has to be serious, that is has to be profound, that it has to be philosophical—and I do believe my work is all those things—but, I also strive for my work to be consumable and for it to talk about these very mundane things that we all experience. We all experience love and heartbreak and yearning for someone. I feel like I’m just living in this reality of we have bodies and our bodies look a certain way. I don’t do it to incite any kind of sexual tension or to piss off republicans. The nudity comes from my admiration and obsession with the male body, that’s just something that I’m very honest with myself about. I worship the male body. I am a gay man. That’s what I love, so that’s what I’m going to do. I do it because this is the reality of my experience.

MM: Catholicism seems to be a recurring theme. Do you still have a relationship with the church?

JP: I don’t practice any religion, but I love Catholic imagery and art and culture. I don’t know if I would call myself an atheist or agnostic. I just don’t practice religion, especially organized religion because I just feel like it’s not the way religion was meant to be practiced. It’s not a part of my life at all, but I fully respect every religion. I wish religions respected me as much as I respect them, but that’s just not the case.

I just really see and acknowledge and am sort of inspired by the way the Catholic church really utilized painting as a social and political tool, and it helps me see how much power there is in images, and so I really see the power in that, through the lens of Catholic history.

“Pasada por el Guadual,” 2023. Courtesy of Juan Arango Palacios.

MM: You’ve lived in Chicago for close to a decade. What makes the city special to you?

JP: In Colombia I grew up in an urban environment, and before Chicago I was always in a rural or suburban environment. Coming to Chicago felt really like home. The whole almost 10 years that I’ve lived here I’ve lived in Pilsen. It being an immigrant Spanish-speaking community is really important to me. I really feel like I’m part of the community. I can go outside and speak Spanish with members of my community, which is awesome.

I hate cars and driving and I love bicycles and Chicago is great for that. And I hate the winter but I love waiting for summer, you know what I mean? It’s this suspense, it’s this tense waiting period. You are depressed and you’re over it and you’re sad and you hate the snow, but then days like today come by where you feel so alive and it makes the winter really feel worth it. That’s what I love about Chicago.